THE PEBBLED SHORE:

A CHILDHOOD MEMOIR

followed by

BIRTHRIGHT: A NARRATIVE POEM

Ian M Emberson 2005

Edited Catherine Emberson 2019

Copyright: The Estate of Ian M Emberson

Ian and his mother

*

Shakespeare Sonnet 60

Like as the waves make towards the pebbl'd shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown'd,

Crooked eclipses 'gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time does transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow:

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

*

Chapter One

Brighton

“No-one can be altogether good in Brighton ,

and that is the great charm of it”.

Richard Jefferies The Open Air

Earliest memories. What are they? Dreams or fantasies or actualities? That first sight of a fire engine charging along Vernon Terrace seems tangible enough and not just the bright red of the vehicle, but even the smell and feel of the sofa I was kneeling against at the time. Others seem vaguer. The funny lady in the park, no doubt an antique statue with bits knocked off; the purple celosias growing in the Old Steen Gardens; the view of the South Downs, green and curvaceous, in the far distance. And mingled with all of these is the sound of the sea, that most melancholy of sounds; each wave slowly gathering force – breaking – and then the curious gurgling and crunching of the big round pebbles as the wave recedes.

Marriage of Percy John Emberson and

Mary Ann Margaret McDonald in 1925

But autobiographies are supposed to need more precise details than these – dates and times and places. So in the conventional manner I begin with the date of my birth – 29th July 1936 – the time somewhere about 5pm in the afternoon, and the place being some nursing home in Brunswick Place, Hove in Sussex. My father, Percy John Emberson, a journalist on the Brighton & Hove Herald , was almost fifty at the time; my mother, Mary Ann Margaret (nee McDonald) almost forty-four. My arrival, after eleven childless years of marriage, provoked something of a surprise. The cartoonist on the paper my father worked for, a man named Mulholland, was inspired to draw a caricature. In order to get the joke it is necessary to know that a short while beforehand an advert had appeared in the paper claiming that Bourn-vita could “do anything”, and also that my father was well in with the church. On the night of the cartoon George Bell, Bishop of Chichester stands with his glasses on the end of his nose and his hands in his pockets saying “I hear, Emberson, that a son is born!”. My father, on the left with a bowler hat and a notepad replies “M'dear Bishop, it was all due to Bourn-vita!”

It is right and just that my father is portrayed clutching his journalist's notebook, for he was one of those men whose profession is their entire life. He married and begot a child in an absent-minded sort of way, and pottered around at various other odds and ends, but the 'alpha and omega' of his life was journalism. Always he was surrounded by papers and press cuttings, rummaging amongst them, stopping briefly to roll a fag, then bashing away at his noisy little typewriter. Any subject which didn't have relevance to his work was immediately rejected. I remember he once made a reference to astronomy (his only reference to it I should imagine) to the effect that complete ignorance of the subject had never handicapped him in fifty years of journalism. He was interested in the law, local government and church administrations, but these all had a bearing on his job. Somewhat apart from these was a fondness for painting; mainly Turner, Constable and the Pre-Raphaelites. This is the only point where our interests overlapped. Some people have assumed that I got my passion for writing from my father, but I know otherwise.

Actually I think all my creative impulses came from my mother. She was Scottish, having been born Mary Ann Margaret McDonald, in a gardener's cottage at Faskally, near Pitlochry in Perthshire. Both her parents were of Highland stock, my grandfather having been born in the so-called Black Isle, which is really a peninsula off the coast of Ross & Cromarty; and my grandmother hailed from the hamlet of Renegour in the Trossocks. However when my mother was still an infant the family moved to Alloway in Ayrshire, which was the village where Robert Burns was born. Here my grandfather took up the post of head gardener at Auchendrane, the home of Sir James and Lady Coates of Coates cotton fame. All her formative years were passed in Alloway. But when she was seventeen the family moved much further south, across the border, to St Albans in Hertfordshire. How this happened is an interesting story in itself, but it can have no place in this narrative. Suffice to say that, until the day of her death at the age of 95, my mother remained totally saturated in Scottish culture. The music she liked best was the Scottish folk songs of Robert Burns; her favourite dances were the sword-dances, the eight-some reels and Strathspeys (which she danced herself long before my appearance). The books she read had to have a setting in Scotland or she grew weary of them. All this had its influence on me. However, one can't escape the pressures which are all around. As her Scottish doctor told her: “You can call him Ian and feed him on porridge, but he'll still be a wee English man”.

The link with Robert Burns was significant, for I can never remember a time when I wasn't aware that there was such a thing as poetry, and scarcely recollect a period when I didn't attempt to compose it. The concept of rhyme and rhythm had an irresistible attraction. But Robert Burns wasn't the only poet I was aware of as my parents were friendly with two living practitioners of the art – Sir William Watson and Andrew Young.

William Watson was a Yorkshireman, having been born at Burley-in-Wharfedale. He went through a phase of relative popularity, but the extreme conservatism of his work meant that twentieth century poetry soon passed him by, and the dust began to gather on his volumes. According to my father, he and his wife lived in a state bordering on starvation. If he relied on poetry for his bread and butter, this is not surprising! Sir William died some while before I was born. However at the time of my birth Lady Watson gave my mother a small bonnet for me. It was in fact so small that it wouldn't fit my head even when I was newly born. None-the-less I have preserved it until this day.

The other poet, the Reverend Andrew Young, was in a very different situation. Whereas William Watson's reputation was in a nose-dive from which it never recovered, Andrew's was steadily on the up, and he remains much admired by a steady band of followers. At the time I speak of, his poetry was little known, and our connection with him arose because he was a minister at Hove Presbyterian Church which my mother attended. It was he who christened me on 4th October, 1936. Although no longer a fundamental believer, I still cherish this fact. The friendship between the two families was very strong, and in fact continues to this day. One one occasion, when I was about three years old, Andrew took me in his arms for a trip around the church hall. We peeped into various cupboards, which were full of broken dolls, and no doubt I was chattering away. When asked later what Mr Young had said to me, I replied that he had said “ah-ha” (a typically Scottish expression meaning 'message received – over and out”). Since Andrew Young was notorious for his lack of small talk, even getting this response was quite an achievement.

*

We used to have a photograph in the family of two young girls standing by a sea-washed groyne. I had no idea who they were but the picture seemed emblematic of those far-off days in Brighton. The girls must have been sisters, judging by the strong facial resemblance, the elder perhaps thirteen, the younger about eleven. Their arms were linked around each others' waists, suggesting a strong bond between them; their smiles seemed too warm and genuine to be merely explained by a wish to please the photographer. Around their feet the tide swirled amongst the smooth pebbles; and beyond a gentle sea broke into warm wavelets. Their young bodies were largely covered by the costumes which modesty then dictated (though even so they were thought of as daring at the time) – the garments reached half-way down their thighs and also to the elbows. Immediately behind them was the wooden groyne itself, a feeble barrier against the potential storms.

We are now so used to seeing this distant time in terms of the greys and sepias of old photos that we have almost begun to think it really was monochrome. But, of course, it was full of colour. Those costumes the girls were wearing – maybe they were brilliant in blues or reds. The parts of their limbs which fashion permitted them to expose, were no doubt tanned to a soft bronze; the groyne would be splashed with bright viridian seaweed, and the distant sea would be greenish blue, broken by the white of the breaking waves. Fifty years earlier Richard Jefferies had thought this spot the brightest and most colourful in the world, and had prayed that “nothing check the descent of these glorious beams of sunlight which fall at Brighton”. I doubt if it had changed much in the intervening years, at least not in this respect.

My childhood memories are mainly of the beach. Of course it lacked sand, not a grain of the stuff ever seemed to arrive at Brighton. Instead there were pebbles – white pebbles, black pebbles, grey pebbles, brown pebbles, blue pebbles – varying much in size, but all worn smooth by the ceaseless action of the sea. It is the sound, rather than the sight of the pebbles I remember most with the crunching as the sturdy fishermen strode along; the curious grading as the boats were drawn out by the sea; and the external sound of the waves on the smooth rounded stones – reaching forwards, then breaking – retreating. Each action had its own distinctive music.

My mother and myself would spend much time on the beach. She would bathe, and I would paddle around the edge. We spoke to the fishermen and my mother's infectious charm was very effective in breaking down their usual surly, suspicious attitudes. One of them not only spoke to her, but supplied her with weather forecasts, and these she telephoned through to one of the big London papers thus providing herself with a regular source of spending money. Sometimes she failed to find the fisherman, and made up the forecasts herself. I don't doubt they were as accurate as such things usually are.

Not all the boats on that pebbly shore were fishing smacks, some were pleasure boats, taking holiday-makers on short trips out to sea. The most famous of these was 'the Skylark' and in fact the words “Any more for the Skylark?” became a sort of catchphrase for Brighton beach. I expect these pleasure boats brought in more income than the fishermen ever dreamt of and, in fact, pleasure was Brighton's main activity, being its equivalent of heavy industry. Apart from the beach itself, this was catered for by the two piers – the Palace Pier and the West Pier (the Chain Pier once depicted by Constable, had been washed into the sea many years ago, and the demise of the West Pier lay in the distant future).

The obvious thing to do on the piers was to walk to the end, admire the sea view, and walk back again but there were other diversions along the way, such as the distorting mirrors, capable of flattering folks into thinking themselves slim, and vice-versa. Above all there were the penny-slot machines. My favourite was The Haunted House. At first the elegant drawing room would appear calm and sedate: then a cupboard-door would open to reveal the inevitable grinning skeleton; a floor board creaked, and a terrible spectre reared its head; and finally a poltergeist would wreak its invisible devilment on the bookcase. Any child, hearing its copper penny roll down the slope to trigger such delights, would count it money well spent.

The inland parts I remember less well. Brunswick Place, where I had been born, was in the part once known as West Brighton, and now called Hove, and strictly speaking outside the borough boundary. The Old Steine Gardens, where I remember the celosias blooming were close to the Palace Pier. Nearby was East Street, where my parents had rented a flat immediately above the Irish Linen shop. It was no doubt there that 'history was made by night' in Mulholland's phrase. Shortly before my appearance they shifted to another flat in Vernon Terrace, to one of the roads radiating from The Seven Dials. All I can remember of the place, apart from the already-mentioned fire engine, was the birds singing in the trees around Monpelier Crescent, immediately opposite. After about two years they moved even further inland, to a house in Tivoli Crescent, from whence there was a view of the curving green slopes of the South Downs. Somewhere in the vicinity was a winding road which we called 'Snaky Lane' (I don't know its real name). On one occasion I went for a walk down Snaky Lane in the company of my father and clutching a golly (this was in the days when golliwogs were considered suitable toys for children). At some point I realised to my horror that Golly was no longer with us. We retraced our steps for what seemed a vast distance, and I can still remember my relief when I beheld Golly lying unharmed in the gutter. The other two memories of my father from this time are also connected with minor disasters. On one occasion he decided to have a go at bathing me. Unfortunately I had discovered that by moving one's body up and down the bath in a particular way it was possible to set up a wave which rapidly assumed tidal proportions. This I proceeded to do, and managed to soak my father to the skin. On the other occasion I was left in my father's keeping whilst suffering from some minor ailment. Dad rummaged in the cupboard, and came up with a bottle of medicine which he thought appropriate for my condition. On my mother's return, however, she was furious, saying that the medicine in question had been lying around for years and years. None-the-less I survived!

Of course we were not confined to Brighton. When only a few weeks old I was taken in a Moses basket to be exhibited to my mother's family at St Albans in Hertfordshire. What they thought of me I have no idea, but a photo of my maternal grandmother holding me in her arms survives, and she looks at me fairly benevolently.

Ian and grandmother McDonald

Many members of the McDonald family had emigrated to Australia and America, and these branches seemed to be highly procreative. For some reason the ones that stayed at home had numerous childless marriages and no doubt I was something of a novelty.

Back at Brighton the round of frivolity continued. There were picnics on the Downs, and I can still remember the thrill of being amongst these vast curving grassy hills, with the white gritty chalk showing through here and there. Then I was taken to the office of the Brighton & Hove Herald, and allowed to walk along the platform beside the big printing-press. This was something that even my father had never done. Next I was taken to a concert at the Dome, that curious construction which, along with the Royal Pavilion, represents George IV's concept of an Indian palace. Of the concert itself I remember nothing.

And then there was the event which left the most tangible evidence – a visit to the photographers. There I was captured in the various poses, with piles of bricks, cuddly toys and all the other paraphernalia of a photographer's studio.

Caption Studio photograph

I gather from photographers that, parents in those days would rush their first offspring to the studio on the least excuse. The second child might pay a visit at some point; the third even more tardily. As for the fourth upwards, if the most fleeting snap survives it is a miracle. But I was the first and only and, like most such beings, was more captured on camera in my early childhood than all the rest of my life put together. There were photos on the beach, in the park, outside the newspaper office etc, and in fact there seemed to be scarce a scene in Brighton that didn't serve as a backdrop.

All this suggests that at this stage my parents were fairly affluent ( things went downhill later on). The impression is strengthened by the fact that we actually had a maid called Mary Phillips, from Shiremoor in Northumberland. Why Mary and her husband Bob had drifted so far south I'm not sure, but it was probably the search for work, for the Tyneside area still had high unemployment. Bob was a builder by trade, and a red-hot Socialist with hair and a beard which matched his politics. He would preach his gospel at street corners, and, in his quieter moods, come round and tidy our small garden. He was to feature again in my life many years later, after the death of his first wife, and when he was courting his second – also a Mary. By then he had shaved off his beard and subdued his politics. I discovered him to be one of the most likeable men I ever knew and also one of the most talkative.

*

Looking at these childhood pictures of myself, and remembering the photo of the two lovely girls paddling amongst the pebbles, one might be tempted to think that the mid-1930s were some sort of Golden Age. But really and truly was there ever a Golden Age? Athens is supposed to have experienced the phenomena and likewise Florence and Edinburgh. The blissful time in Edinburgh's history is usually dated as the late 18th and early 19th centuries – the age of Adam Smith, David Hume, Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott. I remember seeing an old print of about this time depicting a wretched young mother hurling her bastard bairn into the Town Loch. Did the unhappy child, as its tiny body sunk into the icy waters, draw any comfort from the fact that its brief lifespan had coincided with a Golden Age? I think not. Golden Ages in fact only come into being in the minds of men and women when a bad period of history is succeeded by an even worse one.

Only in the cynical sense could the year of my birth, 1936, be thought of as a Golden Age. It saw the brief reign of Edward VIII and 'Queen Wally' as some people referred to Mrs Wallis Simpson. The denouement of this tragic comedy was the Abdication crisis. No doubt it was a storm in a teacup, but it succeeded in shipwrecking the Archbishop of Canterbury's plans for making the Coronation into a reassertion of Christian values. More serious was the mass unemployment, somewhat eased by 1936, and limited to individual areas, such as Jarrow. In the autumn the Jarrow Crusade marched to London, carrying with them their petition to Parliament. But they got little compensation for their tired limbs and blistered feet. Within a short while of their arrival the papers were full of the monarchical crisis, and the fate of men and women whose dole money kept them scarcely above starvation was forgotten. Worse than any of these, both in itself and what it prefigured, was the Spanish Civil War, which broke out ten days before I was born. The Republican Government was not only fighting against the forces of Franco, but also the combined might of Hitler and Mussolini. It is sad now to read of the efforts of men like Arthur Henderson and George Lansbury to achieve universal peace and disarmament. Their striving coincided with the rise of Fascism in Europe. The forces thus set in motion came to their inevitable conclusion – the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

There followed the so-called 'phoney war' when much was feared, but little happened. The main fear was for the big cities and the south coast, as the most likely areas for attack, and so the evacuees, the women and children, started to pour out into the countryside. Most of this evacuation was officially organised, but there were also the 'unofficial evacuees'. My mother and myself fell into this category. With an unseemly haste, for which my mother always bore a grudge, my father packed us off to my maternal grandmother's home near St Albans in Hertfordshire. For reasons I still don't fully understand, my parents lived apart for the next fourteen years. They weren't separated in the usual sense, and visited each other regularly. Perhaps the clue is in a backhanded compliment my mother once paid my father: “he would have made a first-rate bachelor!”

Of course we came back to Brighton on visits, and it is possible that some of my above-mentioned memories relate to these later visits. Once of these wartime recollections predominates – the sight of Brighton beach. No doubt we have now grown hardened and somewhat immune to the images of war – Hiroshima, Dresden, Belsen and Auschwitz. But this image is of a different aspect of the conflict: the sunlight beating down as gloriously as ever and the waves breaking on the pebbled shore. But where are the children who should be running, and bathing and shrieking with delight? Not one – not a single one. Instead there is nothing but endless coils of barbed wire, with land-mines buried beneath. This for me sums it up. The sheer waste. The stupidity of it all.

Chapter 2

NEW RENEGOUR

And so it was, that at the age of three, I found myself in a new home, a home which was more a part of the countryside than I had experienced before. My maternal grandmother's house lay about a mile to the south of St Albans in Hertfordshire. Nearby lay the route of the old Roman Road called Watling Street, which stretched from what was once Londinium (London) in a north-westerly direction to Viroconium, Wroxeter, near Shrewsbury). Close to my new home had once stood the city of Verulamium, fragments of it still remained; a few outcrops of the ancient walls, the hypocaust, the theatre and the beautiful scallop shell mosaic, now housed with lesser treasures in the museum. Far more important to us children were the Verulamium Woods – actually part of the moat of the city, now overgrown with beech trees. We loved to play there, running down the steep slopes and letting the momentum carry us almost to the top of the other side. In the evening the woods became a favourite roosting place for tramps, and we would see the blue smoke wreathing upwards through the trees as they cooked their frugal meals, before laying down to sleep amongst the ramparts that Roman sentries had guarded two thousand years ago.

Our house was called Renegour, or more precisely New Renegour to distinguish it from Old Renegour on the other side of the road and both places were named after the hamlet in the Trossachs where my maternal grandmother had been born. My grandparents had moved from the old house to the new one about nine years previously, and grandfather, a professional gardener, had laid out the pear-shaped flower borders in the front garden. Perhaps it was the move which finished him off, for having been a strong, healthy outdoors man for eighty years, he abruptly died of a stroke a few weeks later. The family I thus came into was thus deprived of any masculine leadership, and consisted of my grandmother, my mother, myself, and my Aunt Elizabeth, who at that time was unmarried.

The house itself was fairly undistinguished, and typical of many built in the 1920/30s. It was part of a straggle of houses which lined either side of the Watford Road to the south of the King Harry public house. Between the road and the front gate there was an area of rough grass which was a favourite haunt of Holly Blue butterflies. The main feature of the front garden were the above-mentioned pear-shaped borders. Apparently this was a favourite feature of my grandfather's. The hedges of variegated privet were conventionally shaped – topiary work was one of his great hates. The house itself had an arch over the front door, a bay window across the dining room with cotoneaster growing beneath - its flowers much loved by the bees, and a dormer window protruding from the small bedroom above. To one side was an overgrown shrubbery which we children referred to as 'the forest'. The back garden was long and thin. To one side was an air-raid shelter. I scarce remember it being used for its official purpose. My main recollection of it is as a store-house for apples – and the aroma of slightly gone-off apples is always associated with it. Beside the air raid shelter was the lawn, and the bottom of the garden was given over to vegetables, which was our contribution to the 'Dig for Victory' mentality.

*

No doubt the reader will now expect a long passage about the horrors of war – the bombing raids, gas masks, food shortages, rationing etc. But this expectation overlooks one essential element in childhood – a child's capacity to accept. No matter how bizarre its outwards circumstance, in a curious way which adults can't understand, a child considers it somehow normal. The Second World War started when I was three and ended when I was nine. By 1945, wartime constituted virtually all of my remembered existence. I recollect my father commenting on a boy who had died young that “he had never known a normal England”. Yet what is a normal England – a normal family – a normal anything? On close examination 'normal' things usually prove to be as rare as albino blackbirds. The war was on and that was that. But for most of the time it was background and nothing more.

*

Once the 'phoney war' was over the bombing began in earnest. We were sufficiently close to London to be able to see the glow in the night sky as the bombs fell and the houses burnt. We would stand at the back windows, and look across the dusky, peaceful farmland, at the red shimmering reflection to the south east. Then, having looked our fill, we would go downstairs and snuggle into our 'house beds'. These 'house beds' consisted of some blankets and sheets laid out beneath a table. Thus ensconced, even during a bombing raid, I felt in my infant mind totally safe. My mother, aunt and grandmother were all close by, and I was protected by my house bed – so all was well. The idea that one of the bombs might come through the roof and kill me never entered by head.

This naïve attitude is well illustrated by an incident which happened on one of our visits back to Brighton to see my father. Ironically, shortly before the outbreak of war, my parents had moved to a larger house in Tivoli Crescent, to the north of Brighton and close to the South Downs. It was here that my father carried on his bachelor existence, with occasional visits from his wife and small son. In this particular visit I discovered to my joy that there was an anti-aircraft battery at the bottom of the crescent. Of course we had to visit it. Later I did a memory-painting of the scene. In the middle are two big machine guns, with the gunners at the ready. Around the battery is a low wall, with my parents and myself looking over it, whilst the sentry at the gate salutes us smartly (this last must have been a flight of the imagination).

As I remember things, it was on the night following this visit that there was a big bombing raid on Brighton. The bombs exploded all around; the machine guns at the bottom of the road rattled incessantly; and the whole house trembled. We were all 'sleeping' in the one room; my parents in the big bed, and myself in a small bed in the corner. Needless to say no-one actually slept, and my mother was lying awake thinking what a terrible experience this must be for a her small son, when a joyful voice came across from my corner: “I say, Mummy. Isn't it interesting?”

Back at home the war effort was of a more mundane nature. What little I can remember of the Home Guard suggests it was even more farcical than 'Dad's Army' – a bunch of old codgers who couldn't have kept back a herd of cows, never mind the German Army. There was also something known as 'Fire Watching'. The idea was that every adult would at least know how to put out an incendiary bomb. A man who was in charge locally was a notorious womaniser, who used his Fire Watching rota as a cover up. On one occasion it was decided to practice putting out a bomb, and the location selected was the rough area of grass in front of the house (an incredible spot to choose, with a main road on one side and a row of houses on the other but I know for fact that this was so).

It was lateish on a summer evening and I was supposed to be in bed and sound asleep. At the appointed time, however, I got out of bed, climbed into the dormer window, and viewed the scene with intense interest. On the patch of rough grass lay the bomb. Whoever was in the charge of its ignition was generally messing about, whilst my mother and aunt stood to one side with the garden hose. My excitement was short-lived. The incendiary device proved to be the most peace-loving bomb in the history of warfare and I have seen many a firework that was more aggressive. The problem was not the putting out, but getting it lit in the first place. I soon lost interest and went back to bed.

For the most part we just plodded on with our usual lives, dealing with whatever came along, such as learning to wear Mickey Mouse gas masks that had been issued. In practice it was on the 'dig for victory' side that the ordinary citizen made the most positive contribution. Thus, in a truly patriotic spirit, we consumed vast quantities of spinach and raw carrots, and drank down gallons of water in which the vegetables were boiled; knowing that each gulp and munch, we were somehow “beating Old Hitler – Hurrah!”

Chapter 3

EVACUEES

One obvious impact of the war that affected everyone was the sudden appearance in the provincial towns and villages of sudden swarms of evacuees. Like locusts they came – from the southern coastlines and the big cities, fleeing the wrath to come. Thus quiet middle-class families abruptly found they had billeted on them a group of kids, of whose very existence they had been unaware the previous day. Many anecdotes were told of this great mingling together, and in the particular of the working-class townies' first reaction to the countryside. My favourite tale (probably apocryphal) is of a little London girl who came across a heap of broken milk-bottles, and thought she had discovered a cow's nest!

Of course my mother and myself were evacuees of a sort, but of the train loads of uprooted children pulling out of the big London stations I know nothing. I rather saw the evacuation from the other angle – from that of the families who suddenly found strangers being billeted onto them.

The first instalment consisted of a Mrs Viner, and her two sons, Gordon and Malcolm. Mr Viner wasn't in the Army, but in one of the so-called 'essential industries', namely an aircraft factory near Bristol. I think their stay must have been brief, for I can remember very little about it. My chief recollection is of a visit from Mr Viner, and of him bringing along a collection of what we called 'nuts and bolts and squiddy bits'. These were divided between Gordon, Malcolm and myself. Alas I do not even retain a single 'squiddy bit' to remember them by.

The second and final instalment of evacuees was the Wakeley family, consisting of Mrs Constance Wakeley known as Stancia) and her two children, Elizabeth and Richard. Their father was in the RAF in India. They stayed with us for what seemed like an age, but couldn't have been longer than five years. Although two rooms were exclusively the Wakeleys, for most purposes we constituted one family, and a very matriarchal one at that: Mrs Wakeley, my mother, my aunt Elizabeth (my grandmother had by now passed away) and we three children. So integrated was the 'family' that my father gave equal amounts of pocket money to each of us, and I felt no resentment at all.

Mrs Wakeley was a Londoner from Dulwich and a woman of great charm and sincerity, a fair bit younger than my mother. Whilst my aunt was out working the two women shared the tiny kitchen but there was, apparently, never an ill word. Elizabeth was a little older then me, and something of a tom boy. She wasn't conventionally pretty, but her face had a strength and determination which marked her character. Richard, a year or so my junior, was a complete contrast. I recollect him as he was when he first came to the house as a weak, pale-faced little boy, with a light-excluder over one eye, and with his nerves badly shaken by the bombing raids he had experienced. Late one afternoon there was a violent thunderstorm. All my life I have enjoyed thunderstorms – the bigger the bangs and the brighter the lightning, the better I liked it. Richard, however, screamed the place down, mistaking it for a bombing raid. An even more unpleasant memory is of an occasion when I suddenly felt a spasm of jealousy towards this small boy who had usurped my place as the focus for female adoration. Without more ado, I seized him by the shoulders, and began banging his head against the horse-hair sofa. Even after sixty-plus years I find the recollection painful.

*

One point of which my mother and Mrs Wakeley had very different attitudes was in their feelings towards the local farming community. Mother had been brought up in rural Ayrshire. She was the daughter of a gardener; and most of her fellow pupils at Alloway School were the sons and daughters of farmers. Farms were places you took for granted: when passing through them on country walks, the dogs barked and the cows mooed and that was that. Not so Mrs Wakeley. She looked quizzically on the local farms and minor zoos and took us kids round them very much in that spirit. One might have expected the farmers to be hostile to this lady with a strong London accent, turning up with her retinue of kids, and leaning over the pig sties, and peering into the darkened cow-sheds. But not a bit of it. She had such a way of ingratiating herself, that we were soon on friendly terms with all the local farming families.

I remember the farms, not by their proper names, but by the names of the families who owned them. Thus there was Shepherd's Farm, Muir's Farm, Pope's Farm etc. All I recollect of Shepherd's Farm was a small duckpond which usually dried up in the summer, leaving nothing but caked mud and disgruntled moor-hens. Memories of Muir's Farm are more vivid, for its fields lay just beyond the garden fence. There was one plank of the fence which was missing, and never replaced. This meant that by placing one left foot on the horizontal strut, and swinging your right leg over, you were into the field in a twinkling. The great delight of this spot was watching the three big carthorses, Bob, Jess and Dobbin, grazing the touch chalky grass. Bob and Jess were both whitish grey, whilst Dobbin was brown, and had the curious habit of sleeping standing up.

Beyond the first field was a row of elms (such a feature of the Southern landscape before Dutch Elm disease took its toll), then another field, and finally the farm itself. I remember it as a tumbledown affair, with most of the buildings leaning one way or the other. Even now I can never read Edward Thomas's poem Tall Nettles without thinking of one corner, where old ploughs and tractors rusted steadily amongst a plethora of weeds. The barn seemed vast to my childish mind – like a great cathedral, filled with that wonderful aroma of slightly dampened straw, and dust that tickled your nose and made you sneeze.

In addition to Bob, Jess and Dobbin, the farm also owned four fat little grey ponies, whose names I now forget. Curiously enough they were housed in four separate little stalls dotted around the farm, not in one stable. Their purpose was, of course, the milk-round, pulling the little carts loaded with crates and bottles. We three children used to 'help' with the milk round, though I am sure we were more trouble than we were worth. None-the-less the indulgent young lady in charge somehow put up with us. Every so often the pony would pause, and a steady plopping sound would announce that some rich steaming manure was being deposited on the roadway. This was a signal for a small boy to rush out of a nearby cottage, armed with a bucket and shovel. After a vigorous scraping, he would return proudly to his home with some good nutritious fertilizer for the vegetable garden. No doubt this was also a vital part of 'beating Old Hitler'.

Most visibly of all I remember Pope's Farm, for it was the one we visited most often. One of its attractions was a large flock of sheep, which one took delight in watching, peaceably grazing the dark green pastures. Then there were the horses, very beautiful animals as I remember, dark and sleek. But most of all I recollect the pigs, for there seemed to be vast numbers of these snorting creatures, with a long row of styes on either side of the farmyard. One day as we admired some piglets, a large boar suddenly put his trotters over the half-door behind, and stared at us. “He's going to the butchers tomorrow”, said one of the farmer's sons. Despite his ugliness I felt very sad to think that his remaining time of earth would be so short. It was one of a number of evidences of death which impressed themselves on my childish mind, such as the dead calf lying at the bottom of a small chalk-pit, and the abandoned kittens by the roadside. Thus, even in the midst of childhood, one is aware of the transitory nature of all things.

Chapter Four

EDUCATION

Education – a vile word to ears of some. But here, of course, I speak of formal education, that vast industry concerned with standards, assessments, tests, exams, placements and all the other great weary land of nonsense. I was once at an exhibition of paintings by very young children – the pictures brimming over with that infantile delight in shapes and colours which spring direct from the childish imagination. The man stood beside me remarked: “Oh, these were done before eduction had ruined them”. The irony is that the speaker was the Chairman of the local education committee. I have known music students who, by the end of their university course, had come to hate music. The pressures of studying for exams had completely destroyed their original love of the subject. The last thing on earth that they had wanted to do of an evening was to go to a concert or put on a record. To describe their course as a waste of time is putting it mildly, for it is something far worse. It has ruined the very enthusiasm it was supposed to enhance. They were better off when as young children they bashed randomly at the piano keys, and took pleasure in the cacophony of discords that resulted from their efforts.

Yet all men and women are educated after a fashion – the Hottentot and the Bushman no less than the Varsity don – for the things we need to know are all around us. Thomas Bewick, as a young boy, played truant from Ellerington School, but he was gaining education. Those who remained within the dreaded walls got only beatings and bad Latin. Young Thomas saw the sparkling flow of the River Tyne, the oaks and ashes on its banks and the birds and beasts that populated the area. On a day's adventuring he would observe the scenes, and store them in his memory, thereby laying up that treasure house from which sprung the wonderful wood-engravings of his later years.

But this somewhat personally jaundiced view of formal education is mainly based on impressions received in adult life. Little of it comes from my own early days, and least of all does it derive from my first school, which I attended from the age of four to eleven. This was a somewhat cranky private establishment named Lyndale. It was ruled over by an elderly spinster called Miss Shearn and, like most things during the war, it was very much a matriarchal establishment. There was however Mr Arkeld, a young athletic-looking fellow, who would suddenly arrive and take us boys for sport. I think he must have been a relation of one of the teachers on leave from the army. We boys worshipped him like some sort of distant hero. None-the-less his appearances were brief and unpredictable. For the most part we were entrusted to a group of females, varying vastly in age, and who seldom stuck to the subject, and went off at various tangents , depending on their particular loves and hates, thereby helping to lay the basis for that vast stock of useless information that is with me yet. No doubt a modern inspector would have had the place closed down within a week. In other words, in my simplistic view, it was an excellent school!

I still remember my first day, or rather morning, for I was broken in gently. I was four and three-quarters, and found myself in a large airy classroom amidst a sizeable group of would-be scholars. We were in the charge of an elderly lady named Miss Hull and there was also a young female named June wandering around, performing various duties, though I can't now remember what they were. Miss Hull had white hair tied in a bun, and was rather distinguished-looking. The lesson that morning was 'The Garden of Eden'. Miss Hull listed all the beautiful flowers which grew there, and then said: “But children, there was one thing which didn't grow in the Garden of Eden. Can you guess what it was?” Various hands shot into the air “Cauliflowers, Miss?”, “Brussel Sprouts, Miss?”, “Spinach, Miss?” She listened patiently then informed us: “No, children, it was none of these, it was weeds”. Thus at an early age the vegetation of the Garden of Eden was impressed on my infant mind. Milton has little to add, but this must have an affect of me, as later on I penned by own thoughts of the subject of weeds.

POEM: A WEED IS A FLOWER IN THE WRONG PLACE

A weed is a flower in the wrong place,

a flower is a weed in the right place,

if you were a weed in the right place

you would be a flower;

but seeing as you're a weed in the wrong place

you're only a weed -

it's high time someone pulled you out.

Like other children I was introduced to the mysteries of mathematics with the aid of coloured counters, and, sixty-five years later, have scarcely progressed beyond them. Then there was reading and writing to be considered. Actually I had been quite precocious in these studies in that I could appear to be able to read from the age of two. However in this I was a complete fraud. What I could actually do was memorise a piece of text that went with a picture in a story book, so that all I had to do was to turn the page, note the illustration, and rattle away. I couldn't really read at all.

“The child is father of the man” - Wordsworth said it all. This very early approach to reading, of finding some good dodge that somehow worked despite not being the correct method foreshadowed much else in my life. Years later I learnt to play the violin and the piano, quite badly in both cases. However I would perform my piece with the score in front of me, and give a passably accurate rendition. But I was basically playing from memory, and using the score much as I had formerly used the pictures in my first story book. Consequently I was a lousy sight-reader, though I had eventually learnt to read in the conventional way.

Another subject which seemed to cause problems was 'manners'. One anecdote was recorded by my father in the gossip column of the Brighton and Hove Herald. The original cutting has been lost, but I think I have a pretty accurate recollection of what it said:

“A four-year old Brighton boy in the very early stages of his education was recently invited for a tea party at the local Ladies Bowling Club. When the buns were passed round, he grabbed one, and immediately stuffed it in his mouth. The lady serving exclaimed: “Don't they teach manners at your school?”. Not fully understanding the question, but wishing to be totally loyal to his school, the boy replied: “They do, but they haven't taught me any yet”. Of course the “four-year old boy” was my good self”.

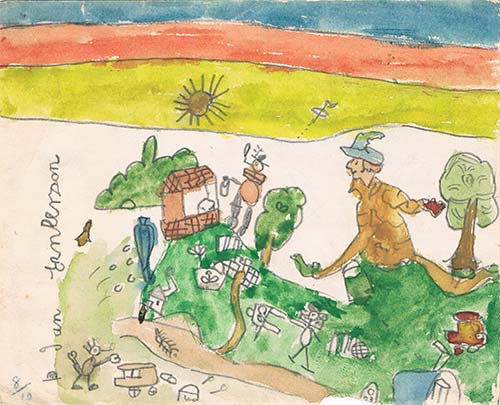

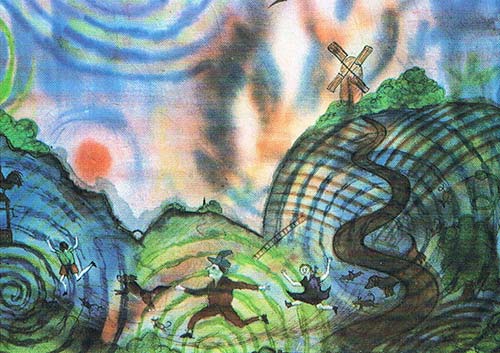

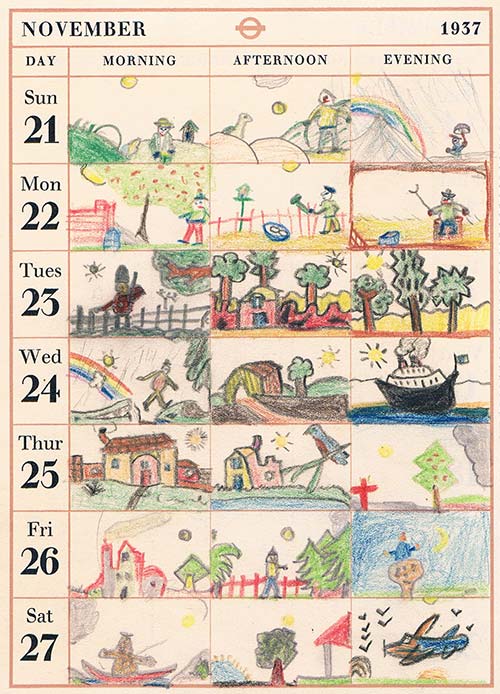

Whilst I was struggling with the basic principles of reading, writing, maths and manners, a teacher of a very different stamp arrived at the school. This was Rosemary Manning – young, beautiful and affluent. Her family lived quite close to us, in a semi-mansion along King Harry Lane. This meant that our routes overlapped, and I well remember the day when she met me in St Peter's Churchyard, and took my hand all the way to school. No youthful lover could have been more exultant! I even managed to ingratiate myself so far in her affections as to be invited to her wedding. A fortnight later she reappeared at school, apparently changed, by some strange metamorphosis into a Mrs Watson. Miss Manning (as I continued to call her) was the first person to encourage me in drawing and painting. The painting of the machine guns at the the bottom of Tivoli Crescent (already referred to) must be a memory – a picture done at school some while later, for the word “good” and the mark 9½/10 appear at the bottom right-hand corner. On the reverse of the paper is a painting of a man in a tall hat running up a hill towards a wishing well. It must be based on some story which had been read to us. Above the running man there appears what I came to call “a Miss Manning sky” - the colours of sunset – red, yellow and blue, although in this case I seem to have got confused and put yellow at the bottom. Fifty years later I based a textile painting on the picture; and this in turn formed the basis of one of my most popular postcards.

Above: Young Ian's painting of the running man. Below: his textile painting done in the 1990s entitled 'Windmill in the Sunset'.

This habit of drawing and painting from memory and imagination was reinforced by Sunday School, where the telling of Bible stories would be followed by a session with paper and crayons. As with so many things the tradition of childhood live on. Sometimes, of course, we would be asked to do a drawing or painting of an actual object, and my efforts in this direction were not at all good. A painting of some catkins has survived and it is a most miserable specimen. There is a note in Miss Manning's handwriting alongside “Bad painting 6/10”. That was a well deserved criticism. No doubt I learnt from my mistakes, and a painting of cabbage done some while later shows considerable improvement.

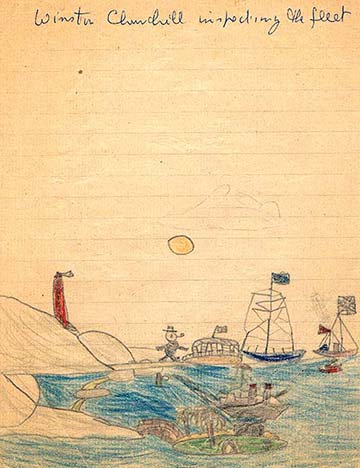

One respect in which these early memories are different from my adult experiences is that I then seemed to be capable of being creative as part of a group, or at least whilst Miss Manning was around to inspire me. Parallel with this I pursued my imaginative world at home. Although basically a sociable child, usually to be found out of doors with my playmates, I can also recall times when I was glad to be alone, and such times were usually devoted to painting and drawing. The pictures I did were similar to those done at school and 'Winston Churchill inspecting the fleet' would have been based on a news item, and shows the great man striding out along the pier, whilst various boats, resembling Spanish galleons, await his inspection.

Gradually, however, the two worlds drew apart. By the time I had reached my teens, all my best painting was done at home, and the work I produced at school was flat and conventional, despite the fact that I admired our new art teacher, Jack Connal. Now the inception of creative work has to be a solitary activity, even though the subsequent sharing is very important. I have known people who are the exact opposite and who can only be creative as part of a group. No doubt we are what we are and there is nothing more to be said about it.

Miss Manning eventually left, no doubt to 'start a family' as they say, and her place in my affections was taken by a lady diametrically her opposite, a Miss Quiggins. Miss Quiggins was by no means young, a dark-haired heavily built woman. Miss Quiggins was never my teacher. I knew her solely through school dinners. Due to the war and the risk of bombing, these were held in a part of the building which was supposedly reinforced, though all I can remember of the reinforcements is certain struts of wood which looked no more secure than my house bed. Under this protective canopy various tables were arranged, each presided over by a teacher. Miss Quiggin's table was a small exclusive affair set in the middle, and I always made sure of getting place at it. Miss Q. was remarkable for two things, firstly her talent at story-telling. Strangely enough I can now remember almost nothing of the stories themselves, but only the pleasure of hearing them. This was a pleasure far more vivid than could be derived from any book story read to ones self. Her second fascinating trait was that she was a vegetarian and was seen devouring various delightful morsels that no-one else seemed to be allowed. In emulation of this I became a vegetarian myself – much to my mother's consternation. Despite many lapses and back-slidings, sixty years on I am still a vegetarian. Thus these two very different lady teachers over long weary years between, still exert a beneficent influence.

Chapter 5

PIRATES ON THE VICARAGE LAWN

These are all early memories of Lyndale. My later recollections are somewhat insipid and no doubt school, like most things in life, was eventually taken for granted.

Far more vivid in my mind are the friendships, some of them originating at school, but then taking on a life of their own. Chief amongst these were the Hubbard boys – the four sons of a local Anglican clergyman. Of the vicar himself I remember little. He was scholarly mainly, who spent most of the time in his study concocting rather boring sermons that succeeded in virtually emptying the church. I do however recall an occasion when a large, hairy caterpillar appeared on the Vicarage doorstep and the Reverend Hubbard emerged from his study clutching a large volume devoted to moths and butterflies, in an effort to identify the creature. His wife was a more practical lady, whilst the four boys rushed around the unkempt Vicarage garden like a bunch of savages.

The ringleader was the eldest boy, John, a daredevil, adventurous type. The other three would, I think, have been more timid had it not been for his leadership. The second son, Lawrence, was my own age, and my closest friend at school. He was, I think, fairly refined, outside of our mock adventures. The third son, Mark, died young in a tragic accident but this was in later years, when the family had moved to Norfolk. The knowledge of this casts a shadow over my thoughts of him, but there was nothing of this at the time. I can recollect virtually nothing of the fourth son, not even his name.

We never played official games like cricket and football – all our energies went into acting out an imaginary world. Pirates were the staple diet. The Vicarage lawn (more noted for its bare scarred earth than for its grass) was a vast ocean; various patches of weeds and overgrown shrubs formed islands; whilst the trees served as the rigging of our ships.

Occasionally we varied things by becoming smugglers or highwaymen. We also had aspirations as mountaineers, though this ambition was problematic, living as we did on the gently undulating chalk-lands of central Hertfordshire. Fortunately there was the roof of the Parish Hall. The main steely-slated roof was the main peak; various out buildings constituted the foothills; whilst there was a high brick wall over an archway which represented a narrow and perilous ridge climb – compared with these Crib Goch and Aonach Eagach were mere trifles. Thus it was that in our imaginings we conquered the Cuillins, the Alps and the Himalayas. I was delighted later on to read that the great George Mallory had also begun his 'mountaineering' on a similar Parish Hall roof. He, of course, went on to bigger things – and never came back.

One curious thing is that in our imaginary adventures we never played out the heroics that at the very time were going on in the skies above our heads, and in the deserts of North Africa. Not once did we pretend to be pilots in the Battle of Britain; or soldiers in Montgomery's campaigns. Oh no - all our adventures related to the past – to act out the present never crossed our minds. Why was that, I wonder now?

Looking back on it now from a distance of over sixty years, I wonder where we got our ideas from. “Nothing comes from nothing...” according to Oscar Hammerstein, so presumably we formed from somewhere notions of what the lives of pirates, smugglers, highwaymen and mountaineers were like. Mountaineering is most easily explained, for my mother had spent most of the time she was pregnant with me reading books on climbing. I almost wonder that I didn't practice rope techniques on my umbilical cord. Furthermore Colonel Younghusband's Everest the Challenge and John Buchan's The Last Secrets were sat in the book case. Of course I didn't read them, but merely looked at the pictures. But the stories would be familiar from my mother's retelling.

The reading of books was not a source of our played out fantasies. I was never a bookish child and neither were the Hubbard boys. I recall once being on a bus as it passed the windows of the Public Library, and getting a fleeting glimpse of a girl sat at a table reading a book. 'What a wretched way to spend one's time' was my reaction. I didn't read a book for pleasure until I was about eleven. The radio was a more likely source, and in particular 'Children's' Hour'. We also occasionally saw films and pantomimes. But quite apart from all this, the young child seems capable of creating a vast mythology out of the smallest stimulus – a process which the adult can only emulate laboriously and painfully. Thus from the sight of Captain Hook in Peter Pan, great sagas of piracy on the high seas can be strung out in all their variants. It needs but the hint, the merest germ or seed, and budding imagination will do the rest. And our fantasies were purely an end in themselves. It would never have occurred to us to be like the Brontë children, and record our self-concocted stories. Yet even that most literary family spent three years playing out their fantasies on the Haworth moors, before they sharpened their quill pens and begun scribbling in their little books, so at least we were in good company.

Chapter 6

ST JOHN'S LODGE

As has been said before, the household at New Renegour was very much a matriarchal affair, ruled over by the triumvirate of my mother, my Aunt Elizabeth and Mrs Wakeley. Visits from men were like the appearance of bright comets – their rarity spreading a lustre. Sometimes Mr Wakeley would appear, home on leave, and clutching his kitbag. This was a great event. Once I remember he brought a collection of Indian seashells. As with the pocket money, these were divided equally between we three children. And then my father would appear from time to time, although I remember precious little about his visit. All I can recollect was that on one occasion he noticed that the back lawn was excessively weedy. He bought some weedkiller, and without bothering to read the instructions, set to work. This consisted of flinging a handful of weedkiller at any weed he took a dislike to – and usually missing. The result was that most of the weeds continued to flourish, whilst the rest of the lawn was dotted with ugly bare patches, as if a bunch of midgets had carried out a bombing raid. More heroic were the fleeting visits to school of the legendary Mr Arkeld. Apart from these, however, the only adult males we got to know were doddery old chaps like Mr Walters, who were only capable of putting out incendiaries that were even more feeble than they were.

The exception to all this was Alderman William Bird, a man who I can never remember referring to as anything except 'Uncle Bill' although not strictly correct at the time I speak of. He was a big broad-shouldered important-looking man – Managing Director of the Sphere Steel Works and exempt from Military Service, as being engaged in work of national importance. Now a widower, I think he had set his sights on his secretary, my Aunt Elizabeth. Any excuse for visiting New Renegour was therefore seized upon.

With most adults 'Uncle Bill' was extremely abrupt, if not downright rude. But he had all the time in the world for animals and children. I've known him shout down the telephone like a machine gun set on automatic, as if there wasn't a moment to spare, and then wander in the garden and spend half-an-hour following and chatting to the resident robin. To myself he showed the greatest kindness, and meant more to me than any blood relation with the exception of my mother. If I asked him a question such as “how does a camera work”, he would go through all the stages, and impress the process on my mind so vividly, I retain it to this day. As a child I even nurtured a fantasy that it was 'uncle Bill' and not Percy John Emberson who was my real father. Of course this was totally groundless, and I now find it amazing to think that I could have imagined such a thing.

The next move in the game to persuade my Aunt Elizabeth to become the next Mrs Bird was to get my mother as his housekeeper. One afternoon we went over to inspect his home, St John's Lodge, a semi-mansion on the far side of St Albans. The impression must have been favourable for the deal was concluded and my mother and myself quickly moved in. I thus suddenly found myself living like the son of a minor aristocrat. After New Renegour, with the families somewhat cramped in a normal sized house, St John's Lodge appeared quite palatial. There was a large hallway, with a cuckoo clock (which I delighted in) and various bronze statutes of scantily-attired females in exotic poses (I gather they had been cast at the Sphere Works – but not as part of the war effort presumably) and a built-in wine cabinet. Despite my 'uncle' being quite unmusical, the large drawing room sported two pianos; a work-a-day model which we children were allowed thump away at, and a 'posh' one, that played amplico piano rolls. The so-called kitchen work was done in the scullery. Upstairs there were four bedrooms, two of them pretty large, and a flight of steep narrow stairs that led up to the attic.

However it is the garden I remember more vividly – all four acres of it. It was divided into five main areas. The front consisted of a sweeping, loop-shaped drive, lined (appropriately) with St John's Wort and with a little bird bath in the middle. The lavish flower garden included a small pond . Beyond a line of Wellingtonias lay the tennis lawn, where my mother and myself used to practice the sport, armed with a couple of carpet beaters. The orchard was enclosed by a high hedge, with a gate in the middle. My memory of it is somehow always linked in my mind with Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Secret Garden. Finally there was the large vegetable garden, which included plum and peach trees and a special enclosure for raspberries.

We even had a small retinue of servants. Various maids came and went and when we first went there the placed actually supported two gardeners, but these were soon reduced to one – namely Mr Chippet, who was usually referred to simply as 'Chippet'. To outward appearances Chippet was a small, miserable, prematurely wizened man, with little to recommend him. However I think there was more to him than that, and we were once rather staggered to meet him arm in arm with an attractive young female.

Thus, at the age of eight, I suddenly found myself living more like the offspring of a Lord, than the son of an impoverished journalist. The whole, vast garden was mine to roam in, either alone, or with a few chosen companions – John and Colin from across the road, two sisters named Patricia and Lorna (tomboy types) and various friends from school including the Hubbard boys, although I can't recall us acting as wildly as we had done in the Vicarage garden. And 'Uncle Bill' treated me like a son. He taught me to play chess, and great was my delight on the rare occasions when I beat him. As a variant we played Chinese Chess with a specially designed set. I remember there was a river running down the board, with particular rules for crossing it. He also taught me Solitaire, which was not normally thought of as a social game, but we would compare notes on how we arrived at the desired result.

'Uncle Bill' was now my official Uncle Bill, since he had finally succeeded in turning my Aunt Elizabeth into Mrs Bird, number two. This, however, seemed to make no difference to the position of my mother and myself, and we just stayed on at St John's Lodge as before. It is perhaps appropriate that my main memory of the evenings is of playing the card game 'Happy Families'. The set of cards were made by myself – blank postcards cut in two – the wording and outline drawing in pencil, the colouring in done with pastel crayon. Being home made, the cards lacked the capacity to slide smoothly in the hands like the professional varieties. Thus when someone asked for 'Mr King the Zookeeper', he might be found adulterously stuck to Mrs Brown the Farmer's Wife. Despite these mishaps we duly sat round the fire, watching the supposedly 'Happy Families' divide and re-unite. So keen was I on the game, I even made a totally separate pack and presented it to Elizabeth Wakeley.

Uncle Bill was a very important man in the community and like most such men, was a member of every committee that could add to his kudos. I remember he had a way of clearing his throat at breakfast-time (which I used to imitate) and then read from his diary a list of all the meetings he would be attending that day. What all these societies were I can no longer recall. Only two linger in my mind: St Albans City Council, and the other was connected with mayoral duties. He had already been Mayor of St Albans once or twice before we knew him, with his former wife as Mayoress, and was to hold the office four times altogether, as well as many lesser positions. Years later, when researching the Jarrow Crusade in South Shields Library, it gave me a curious feeling to read that when the Crusade stopped at St Albans on the night of October 29th, 1936, Alderman William Bird presided over their meeting. My mother and myself were of course invited to all the civic events. I can remember going straight from school to the Mayor's Reception at the Town Hall. The Mace Bearer met me at the door of the Council Chamber, bent low, and asked me my name. I was then announced in his booming voice to the assembled company: “Master Ian McDonald Emberson”, whereupon I walked in and shook hands with my uncle and aunt.

The other thing which lingers in my mind is that my uncle was a Liveryman of the City of London, supposedly a member of 'The Worshipful Company of Basketmakers', though needless to say he couldn't have actually made a basket to save his life. On one occasion my mother and myself, plus my uncle and aunt, all went to the Guildhall for the election of The Lord Mayor of London, being driven there in the mayoral car, which, as I recall, was a Super Snipe. There we sat in the ancient Guildhall, beneath the statues of Gog and Magog, and facing across to the large stained-glass window donated by the people of Lancashire in gratitude for the City of London's assistance during the Cotton Famine. The election is scarcely an election in the actual sense, since the next Lord Mayor has already been decided on, and the procedures acted out are age-old traditions. Two incidents remain vivid in my recollections. One is the actual election itself. The custom here is that each name is simultaneously read out and displayed on a board, and the assembled company respond in a pre-determined manner. Thus when the favourite's name is declared, everyone shouts “all”; with the runner-up, his individual supporters shout “here”. There are then about ten or so hopefuls announced, and the traditional reply is “later”. It so happened on this occasion that the last of the hopefuls had the surname 'Beer'. The day was hot and the procedures lengthy, and I recall how the liverymen relished the double-entendre, as they shouted out at the top of their voices “LATER!”. The other memory is of the very end of the ceremony. All the officials clutch little posies of flowers – this being a relic of the days when the party processed to the Guildhall by barge, and the Thames was little better than an open sewer. On leaving, the officials present the bouquets to any lady in the audience who take their fancy. Great was my mother's delight when the Recorder of the City of London strode across to her and presented her with his posy.

*

These are the outward events of childhood. There is also a certain inner world, a matter of shifting antipathies and allegiances, that help to shape, for good or ill, what we will be as adults. During the remainder of the chapter I will try to chart early tentative reactions to religion, music, art and literature.

Religion played a big part in my childhood, for my mother was a very religious woman, and these were religious times. As mentioned earlier, she was a Presbyterian. On moving to St Albans however there was no such church, so, like most Presbyterians, she allied herself with the next best thing – the Congregationalists – the denomination my father had been brought up in. The Congregational Church was a plain building in Spicer Street, an ancient roadway lying close to the great Cathedral. Of the church itself I recollect virtually nothing as my memories are all of the adjoining Sunday School, with its large hall covered in Bible prints and the big, curtained stage at the far end. There was also a certain indefinable smell peculiar to Sunday Schools. The scenes I recall are not especially sacred. They include the singing games we used to play, such as 'The Big Ship Sails through the Alley-Alley-Oh', which involved us all joining hands and passing beneath a human archway. It was rather like a country dance. At other times we sat on our little wooden chairs, listening to a Bible story which we then drew ourselves.

Later a sort of Presbyterian Church was formed, but at this stage it lacked a building of its own. Instead the services were held on a Sunday afternoon in a rather dreary Methodist Church building, at a time when the Methodists didn't need it. There was no Sunday School, so I merely sat with the adults, and 'listened' to the extremely long sermons. This might seem like a very wearisome activity for a small child. However, I utilised the gathering, for this was my time for thinking. What exactly I thought is now extremely vague to me. Yet I know that various abstract ideas formed themselves, and were followed through with arguments and counter-arguments. I don't think this capacity for abstract thought is altogether rare in children. I remember my daughter Beth once told me she recalled having similar experiences. For a few the capacity continues. I surmise that when the philosopher Descartes escaping from the Bavarian snow, sat by an ample stove all day, meditating, and thereby laid the foundations for his whole system of thinking, he was merely carrying into adult life a gift, which for most of us, dies out at the end of childhood.

*

Music was a different matter. I was definitely not born into a musical family. In fact it was almost an anti-musical family. This was partly a matter of history. Mr paternal grandfather belonged to the school of thought that believed one should decide to what their sons should devote their lives to – and that was that. His decision as regards my father was that he should earn his living as a high class draper, and his hobby would be music. It is difficult to know which of the two was the more absurd. All his life he was remarkably shabbily dressed (even worse than myself) and he never allowed so much as a demi semi-quaver to vibrate his eardrum if he could possibly avoid it. The apprenticeship to a high class draper lasted from the age of fourteen until seventeen, when he abandoned the ill-matched profession for journalism, in which he remained for the rest of his life. The violin was abandoned at the same time. His main thought as regards his own son's education was that he shouldn't waste time on music.

My mother was rather different since she had a genuine love of traditional Scottish music, especially the songs of Robert Burns, and the tunes she used to dance to as a young woman. Later in life she developed an appreciation of the popular classics – Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony was a great favourite. But she had no real knowledge of musical theory or of the classical repertoire. My Uncle Bill, in so many ways a beneficent influence, was even worse in this respect. I think the two pianos were a residue from the first Mrs Bird, for the second holder of the title disliked all music, especially if it was loud.

Children are very quick to pick up on the negative attitudes of influential adults and are very ready to learn which activities can safely be regarded as subjects for ridicule. I inherited this feeling as regards classical music. I somehow had the feeling that the great composers were a bunch of pale-faced, long-haired wimps, forever sighing over girls who had the good sense to reject them (perhaps a caricature of Chopin, although I'm uncertain how I knew the original).

Unfortunately the Hubbard boys shared this attitude. We were all great listeners to Children's Hour – mainly for those tales of adventure which we emulated in the vicarage garden. However there was one programme that we only turned on to make fun of – Helen Henschel's talks on classical music. It is lucky the poor woman could not hear us, for no form of abuse was deemed too bad for her. But in the long run it proved to be a case of where “those who came to mock, remained to pray”. To my horror I slowly realised that I was taking an interest in what she had to say, and deriving an unmistakable pleasure in the examples that she played. Needless to say I carefully concealed this heresy from my companions.

The final breakthrough came late one afternoon at St John's Lodge. I was recovering from some childhood ailment, and had come downstairs in my dressing gown, and sat beside the fire. Something was on Children's Hour – not Helen Henschel, but a programme about ballet. Suddenly my attention was riveted. They were playing 'The Dance of the Little Swans' from Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake. It was the opening bars which intoxicated me, and which brought a distinct visual image to my mind – the lake at sunset – the ripples on the water lit by the pink rays – the cygnets crossing the water. I looked in the Radio Times to see when Swan Lake was going to be on, and also listened to other classical music. One day I heard Beethoven's third piano concerto. It was the second subject of the first movement which really captivated me. I thought I had never heard such a beautiful melody. And so it went on and on. I didn't totally escape ridicule. I remember even my Uncle Bill made some mocking remark, which was singularly galling. But the flood gates were now open, and I wasn't going to be put off with trifles.

Along with this developing interest came a growing awareness of a certain blank spot in my nature when it came to performing. For some reason I could whistle, but not sing in tune. The capacity to whistle in tune opened no doors in the musical establishment, whilst the incapacity to sing in tune slammed quite a few. At one point it was decided that some of the pupils at Lyndale School would sing a descant to a particular hymn. I forget which one. Initially I was part of this group. However after a few unhappy attempts, I was politely asked to leave. Later on I learnt to play the violin and the piano – badly in both cases. This love of listening to music, coupled with an ineptitude in performing it, made my subsequent career as a Music Librarian, a well-nigh ideal niche in society.

I had no such hang-ups with the visual arts. Even as a very small child, I delighted in just drawing a crayon across a piece of paper, and seeing some wonderful colour appearing. A certain purpley pink was my especial favourite, but all of them gave an elemental pleasure. This is something basic to the human mind – this fundamental love of a thing – just for its own sake. Later on came the idea of shapes – clouds, trees, animals and human beings and the excitement of linking these shapes with the stories I heard at home, in the classroom and at Sunday School.

Also there was here no parental prejudice to contend with. I don't remember much about my mother's attitude in this respect, but my father, as mentioned earlier, had a genuine love of Constable, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, but I don't think his interest extended much further. The pictures surrounding me, however, were not much calculated to inspire, but then New Renegour was strictly speaking my aunt's home, and the works of art on the walls reflected her taste, or rather lack of it. I recall a large print depicting a monk playing an organ, whilst a shaft of sunlight caught the ethereal figure of a sickly-looking young girl. This piece of sentimentality was entitled 'The Monk's Dream'. 'Moses viewing the Promised Land' was in a similar vein. Far more to my liking was an alabaster relief portraying the climax of Robert Burns' uproarious poem 'Tam O'Shanter'. It depicted Tam furiously riding his faithful mare Maggie across the Old Brig O'Doon, hotly pursued by a swarm of witches, the foremost of whom had just grabbed hold of Maggie's tail. The point was that the demonic females couldn't cross the keystone of the bridge. It was graced with the edifying lines: 'The carlin caught her by the rump/And left poor Maggie scarce a stump'. However it was left to reproductions in books to give me an impression of what real art was all about. The first such picture to make an impression was John Linnell's 'The Last Load' in a school text book. It showed a harvest scene, with the last cartload leaving the reaped cornfield, with a rich sunset glowing beyond. I have never seen the painting since, but I recollect it to this day. Nowadays Linnell's reputation is somewhat eclipsed by that of his son-in-law, Samuel Palmer, but there is a unique magic about his work, and no doubt my youthful self had responded to it.

*

Literature in a sense was all around me in my childhood. My father's profession as a journalist would count for something, though I thought little about it. Then there were my parents' friendships with Sir William Watson and Andrew Young. Perhaps more important that any of this was the fact that my mother had spent her early life at Alloway, which was the village where Robert Burns was born. I gather my maternal grandmother was a bit sniffy about Burns – no doubt an account of his drinking and womanising – particularly the latter. There was some anecdote of a pedlar coming to the door selling his verses, and my grandmother shouting at him: “Get away wi yer – ye and yer Rabi Burns”. However by the time of my mother's generation all this had changed. At Brighton she always attended the annual Burns Dinner, held at the Grand Hotel, and followed by exhibition dances by Miss Margaret Ogilvie, accompanied on the bagpipes by Pipe-Major MacDonald of the First Battalion of the Scots Guards. Judging by the one sumptuous menu which has survived, these were very big 'dos' indeed. On a more sober note, volumes of Burns' poetry were always readily to hand, and records of his songs played on the wind-up gramophone. There was even a bit of wood kicking around the house which purported to be part of Robert Burns' bed, and was no doubt as authentic as most purported items.

As mentioned earlier, I was not a bookish child. None-the-less books were read to us at bedtime. I recall such things as Enid Blyton's Shadow the Sheepdog, and Circus Days Again. I later discovered that these works were sneered at by librarians, but I am not aware that they did me any harm. There were also books we read at school such as The Emperor's Treasure and The Mystery of Mitre Court. I have no idea who the authors were, but the outline plot of the latter is still vivid in my mind. Like the Hubbard boys, I was enchanted by these tales of adventure, but it was the tales themselves which mattered, not the way there were told. In fact even more important than the actual stories was the stimulus they gave to our imaginations to play out adventures of our own. When, at around the age of twelve, I eventually discovered the pleasure of actually reading a book myself, the adventure story was still my staple diet. I actually made a reading list for 1948, and have it before me as I write. Mostly it consists of titles such as The Quest of the Black Opals and The Swiss Family Robinson, although I notice it does include Charles Dickens' The Christmas Carol. However all this lies beyond the scope of the present narrative.

Poetry was a different matter, for here the actual pattern of the words was important. I can't remember a time when I wasn't fascinated by rhythm and rhyme – particularly rhyme. Even today, when I hear a new word, the first question I ask myself is; “What does it rhyme with?”. Meaning is secondary and spelling last of all – not much has changed as my tastes were by no means intellectual. Humorous poems were my favourites. Two of Thackerays' stick in my mind – one about a Chinese sage and his pigtail, the other about action on the high seas. There was also one called The Height of the Ridiculous which I liked so much I even copied part of it into my journal (of which more anon). Occasionally a quieter poem would appeal, such as The Gypsy Caravan which was linked in my mind with the beautiful painted caravan that used to stop by the wild pear tree opposite New Renegour. I also relished various patriotic effusions. I can recall two lines from one such masterpiece: “And we thrashed the Huns at Hartford/To the Glory of the Lord”. This was probably my introduction to war poetry.

All this time I think I was vaguely aware that there existed something called 'serious literature' out there beyond the jingling rhymes and adventure stories. What exactly it was I couldn't have said, yet somehow it was there. At this stage of my life I never read any of it, except in the merest snippets. And even these reconnaissance excursions had a curious guilt feeling attached to them – the feeling that it not not quite healthy or 'boyish'. I might be reprimanded for climbing on the roof of the parish hall, but it would be half excused on the grounds that 'boys will be boys'. Taking an interest in serious literature was another matter.